No More Peace

Notes on class struggle, fascism, and primitive accumulation

I’ve recently been reading Oliver Baker’s new book No More Peace: Abolition War and Counterrevolution (Stanford University Press, 2025) in connection with an undergrad course I’m teaching this term on social movements. The selections I was reading today got me thinking about recent debates around the so-called “originary accumulation” (ursprüngliche Akkumulation) argument in Capital, vol. 1, and its uptake in contemporary social theory. In that spirit, I thought I would take a moment to hash out these debates and how they relate to Baker’s absorbing book.

To anticipate, in Part VIII of Capital, vol. 1, Marx suggests that a historically datable “primitive accumulation” of capital must have operated as an origin and springboard (Ursprung) for the generalization of capitalist social relations in the early modern period. The basic intuition here is that capitalist social relations couldn’t just “spring” out of thin air; they depended on an already-existing social division between those with property (which could be deployed as capital) and those with none (whose sole asset was their capacity to work, which they could sell like a commodity on the labor market). Marx argues that this division—which capitalist social relations posit as a presupposition—stands in need of explanation. And to all appearances, that explanation is what he sought to provide in the section on so-called “primitive accumulation.” I’ll come back to this argument and some of the current debates around it in a moment.

Abolition war and counter-mobilization

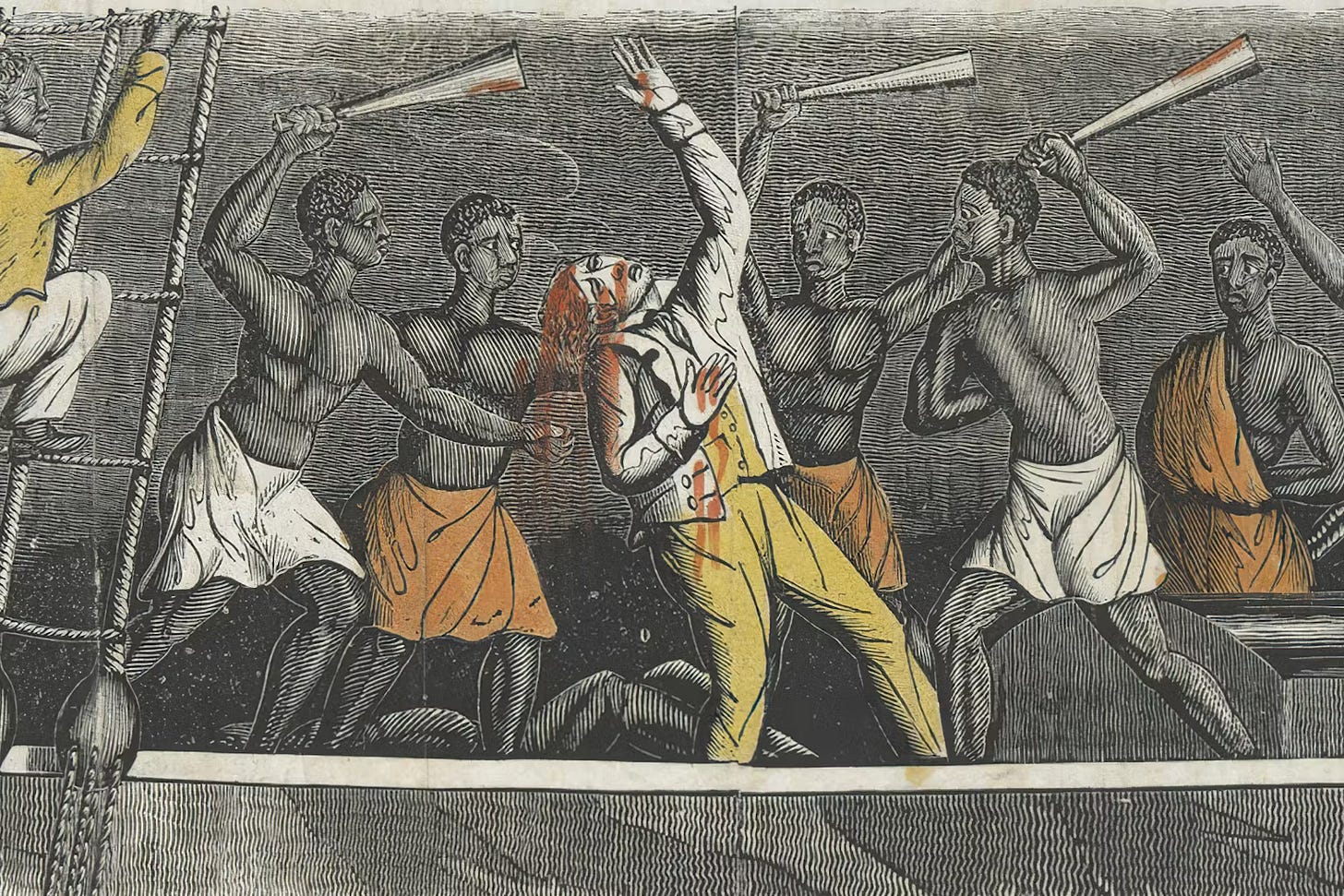

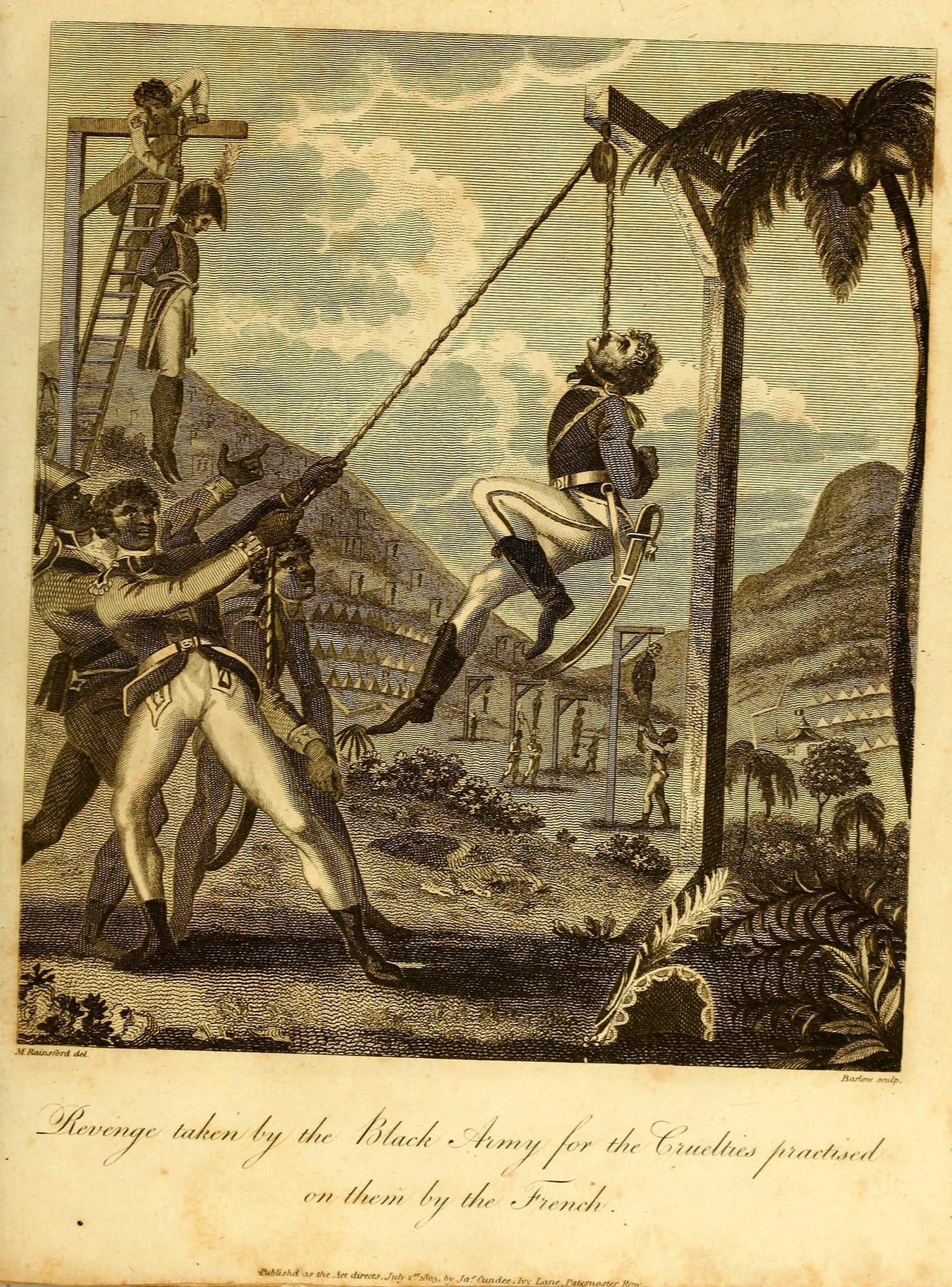

First, I want to discuss a few elements of Baker’s book I’ve found particularly intriguing. At its core, No More Peace reflects a powerful effort to rethink militant nineteenth-century struggles for abolition as co-constitutive with the forms of “white counterrevolution” they provoked. As Baker puts it: “In the dialectic of resistance and repression abolition and anti-colonial wars served as the motor forces in the development of the repressive structures that came to enforce racialized capitalist social relations.” The analytic approach here is roughly Trontian, in the sense that structures of domination are seen as constantly reconfigured and reshaped by agitation and insurgency from below. The dominated classes make history, constantly running up against a social order that adjusts itself to the contours of their resistance. As Mario Tronti wrote in Workers and Capital (1966):

“Working-class struggle has always objectively functioned as a dynamic moment of capitalist development, such that at the level of socially developed capital, capitalist development is subordinate to working-class struggles.”

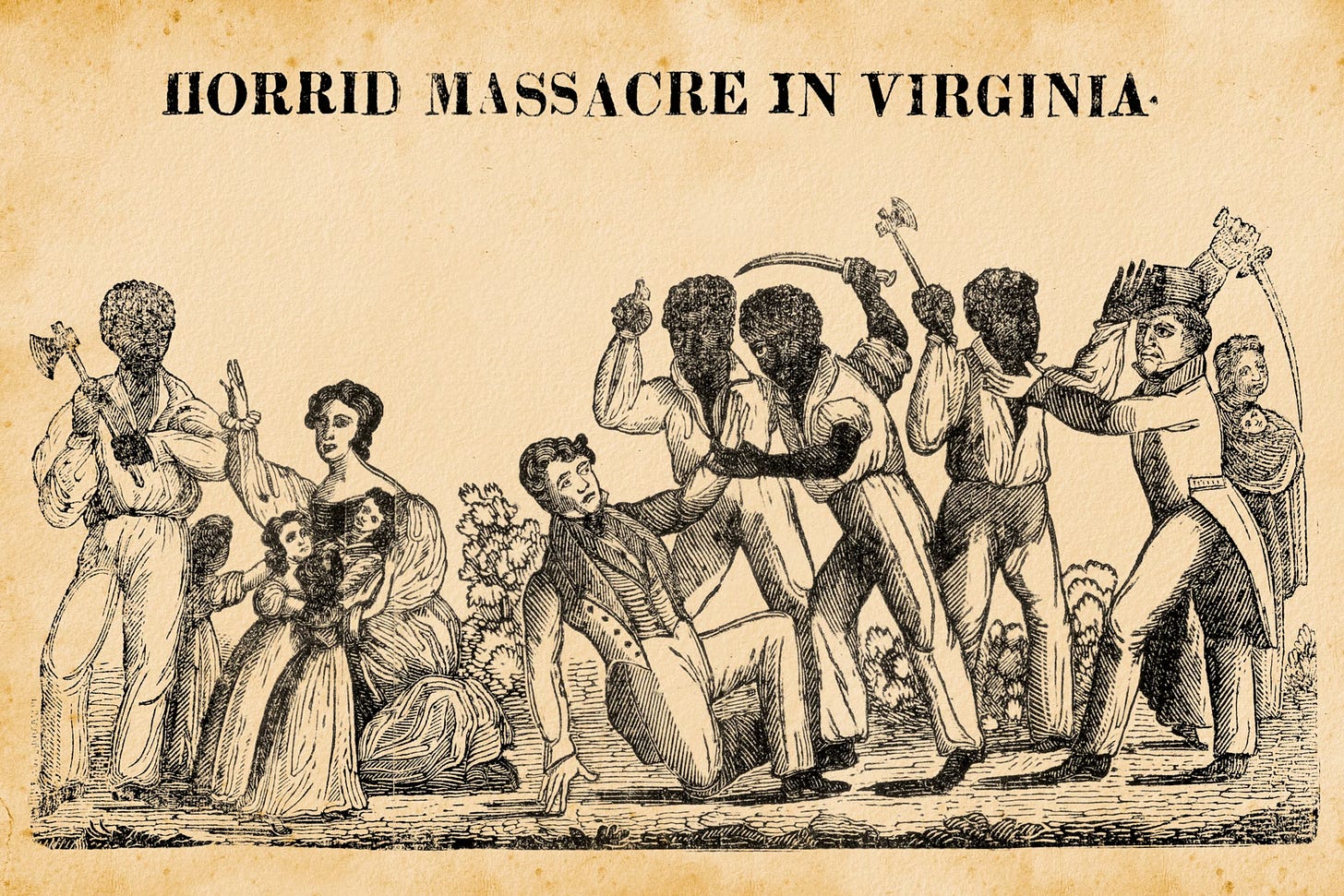

In a similar vein, No More Peace refuses the comforting narrative that slavery collapsed under the weight of its own injustice, became historically obsolete, or was overcome through a “passive revolution” brokered by elites. Baker reconstructs abolition as a violently contested process in which emancipation and reaction were inseparably interwoven. The central claim is not simply that counterrevolution followed abolition, but that counterrevolution’s logics were intimately entangled with “abolition war”—shaping its horizons, its limits, and its afterlives. The historical emergence of the racial capitalist state can be seen from this perspective as a series of “continuously developing counter-formations” against the resistance of oppressed classes.

Counterrevolution is not just the organized backlash of defeated elites, but a durable logic of anticipatory repression evolving in tandem with popular struggle.

What makes Baker’s intervention especially powerful is his insistence that counterrevolution must be understood, to paraphrase Patrick Wolfe, as a “structure, not an event.” Put differently, counterrevolution is not just the organized backlash of defeated elites who reconsolidate in the aftermath of insurgent breakthrough. Rather, counterrevolution names a durable logic of “anticipatory repression,” with legal reconfiguration and racialized state violence evolving in tandem with popular struggle. Thus, in Baker’s account, abolition war generated new political possibilities, but it also compelled ruling classes to innovate new techniques of domination. The emancipatory struggle against slavery functioned as a laboratory for modern counterinsurgency, birthing the disciplinary logics, labor regimes, and frameworks of governance that have persisted alongside what Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlives” of slavery.

Preventative Counterrevolution

In reading Baker on the “anticipatory” logic of white counter-mobilization in the antebellum United States, I was reminded of Luigi Fabbri’s 1921 essay on fascism as a “preventive counter-revolution.” For Fabbri, fascism was not an ex post response to an accomplished revolution, but a frenzied conservative reaction to the threat of emancipatory working-class struggle. In this sense, Italy was experiencing “a counterrevolution without there ever having been a revolution,” triggered by the mere possibility of proletarian elements crystallizing into an insurgent social force. Fascism was a project of anticipatory violence, organizing repression against the potential of revolutionary mobilization.

In Late Fascism (Verso, 2021), Alberto Toscano quotes a 1970 interview with Herbert Marcuse to similar effect. Writing amidst student uprisings, the rise of Black Power, and mass opposition to the American war in Vietnam, Marcuse identified the consolidation of conservative reaction against the counter-cultural movements of the 1960s as a “preventative counter-revolution to defend us against a feared revolution, which, however, has not taken place and doesn’t actually stand on the agenda at the moment.” The mass support garnered by conservative revanchism led Marcuse to predict—chillingly—that “American fascism will probably be the first which comes to power by democratic means and with democratic support.”

Fascism was a project of anticipatory violence, organizing repression against the potential of revolutionary mobilization.

If Marcuse’s words appear uncomfortably prescient today, Fabbri’s analysis ties fascism back to Baker’s work in a way that underscores the continuity between US antebellum history and our present moment of reactionary crisis. For Fabbri, fascism can be understood as a modern permutation of class warfare whose logic extends well beyond the ranks of the fascist movement’s active militants. In his words:

“Fascism, guerrilla warfare between fascists and socialists—or, more accurately, between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat—is nothing but the natural unleashing and material consequence of the class hostilities honed during the war… Fascism is a response to the defensive needs of modern society’s ruling classes… As such, it need not be unduly equated with the official, numbered, monitored and card-carrying members of the Fasci di combattimento. The latter may have provided the phenomenon with a name and blazed a trail for it and furnished its organized central core—which is to say they have done a lot for it—but they have not done everything. In reality, they are not the whole and all of fascism: and occasionally it happens that fascism reneges a number of the presumed ideals and agendas that the first fascists brandished like a flag.”

Similarly, Baker understands “white counterrevolution” in the antebellum US as a project of class warfare—a “counterrevolution of property,” in W.E.B. DuBois’s words—that actively stitched together a ruling-class coalition along racial rather than purely economic lines. Against the destabilizing effects of insurrectionary abolitionism, stable capital accumulation was restored through a process of “white alliance policing” that worked to “manage both revolt and fugitivity as strategies of abolition war.” Far from reducing racial antagonism to an epiphenomenon of class warfare, Baker shows how the former was erected as a structurally reinforcing “pillar” of the latter.

Primitive Accumulation

This brings me back to one of the most intriguing and timely lines of argument in Baker’s book: that abolition war and counterrevolution must be read as “moments of class struggle” internal to the “process of primitive accumulation.” As Baker writes:

“The theory of white counterrevolution helps us think through debates about capitalism’s reproduction and expansion in Marxist thought. For Marx, capital accumulation transforms from the stage of primitive accumulation to mature industrial forms when the relations of production reproduce their own presuppositions.”

Baker argues that once capitalism has achieved its “mature” stage of “expanded reproduction,” the white or metropolitan working classes are primarily disciplined by the “mute compulsion” of abstract economic power rather than the coercive force of the state, which is reserved for exceptional circumstances (strike-breaking, counterinsurgency against organized labor, and so on). In Marx’s words: “the constant generation of a relative surplus population keeps the law of supply and demand of labor, and therefore keeps wages, within narrow limits which correspond to capital’s valorization requirements.”

Put differently, the dictates of the market and the fear of being sloughed off into the ranks of the under- or unemployed tend to check labor militancy and working-class agitation, with the state’s coercive power necessary only as a last resort. By contrast, Baker suggests that in colonial or racialized contexts—or “in capital’s period of primitive accumulation”—subalternized workers are disciplined and governed through more overtly coercive dispensations, of which plantation slavery is doubtless the most extreme example.

In developing this account, Baker both inherits and extends a line of argument well established by scholars of racial capitalism and first worked out by Marxist feminists beginning in the 1970s. Several interrelated positions place the category of “primitive accumulation” at the center of these literatures. What they share is a view of primitive accumulation as not just a datable event in modern capitalism’s prehistory, but as a durable social relation continuously reproduced within capitalist societies. The violent separation of producers from the means of subsistence is not simply a precondition for wage labor—as Marx seems to suggest in Part VIII of Capital, vol. 1—but an ongoing process that must be constantly renewed through racialized, gendered, and imperial forms of dispossession.

The violent separation of producers from the means of subsistence is not simply a precondition for wage labor, but an ongoing process that must be constantly renewed through racialized, gendered, and imperial forms of dispossession.

To give just one prominent example, Marxist feminists have argued that unwaged reproductive work functions as a permanent infrastructure of accumulation, supplying capital with laboring populations whose “production” remains miraculously external to the formal wage relation. Meanwhile, scholars of racial capitalism have emphasized that the racial order is not an accidental residue of capitalism’s origins but one of the central mechanisms through which accumulation is stabilized and inequality rendered governable. For both feminists and theorists of racial capitalism, “primitive accumulation” is understood as the structural underside of “expanded reproduction”—a set of coercive social relations that continuously regenerate the conditions for market dependence, even as capitalism presents itself as a system governed primarily by free exchange or, at worst, abstract economic compulsion.

If scholars of “Black marxism” and Marxist feminists have long stressed the structural persistence of “expropriation” within capitalist modernity, another prevalent approach to primitive accumulation follows more closely from Marx’s own historical line of argument in the relevant sections of Capital, vol. 1. In Chapter 26, Marx describes the “originary accumulation” of capital as something like “original sin in theology”: “from this original sin dates the poverty of the great majority that, despite all its labor, has up to now nothing to sell but itself, and the wealth of the few that increases constantly although they have long ceased to work.”

Presumably, Marx has foremost in mind the enclosure of the common lands and the immiseration and proletarianization of the European peasantry. Thus, he describes primitive accumulation unequivocally as

“those moments when great masses of men are suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled as free and ‘unattached’ proletarians on the labor-market. The expropriation of the agricultural producer, of the peasant, from the soil, is the basis of the whole process.”

Yet, Marx immediately qualifies this general point, noting quite rightly that “the history of this expropriation, in different countries, assumes different aspects, and runs through its various phases in different orders of succession, and at different periods.”

This qualification has sparked off a proliferation of historical studies of the roots of capitalism. The general argumentative drift of this work is well captured by Melissa Naschek: “the West became rich and economically developed directly as a result of colonial plunder — colonial plunder was essentially responsible for bringing about capitalism.” From this perspective, the “original sins” of capitalism—its Ursprünge or points of genesis—are colonialism and slavery. Without these originary moments of expropriation, the machinery of capitalist exploitation could never have been set in motion.

Plunder and the origins of capitalism

Vivek Chibber has recently launched an acerbic attack on this view, which he associates with retrograde elements of the academic and para-academic left whose commitments to “racial identity politics” make them especially susceptible to this sort of “nonsense.” In Chibber’s view, the account of capitalism as engendered by colonial plunder is an unsustainable and fundamentally flawed historical hypothesis that collapses under both empirical scrutiny and Marxist theoretical analysis.

To advance this thesis, Chibber takes a two-pronged approach.

On one hand, he argues that the historical record does not support the claim that wealth extracted from colonies was the engine of capitalism’s initial development. This is basically an empirical point. Spain and Portugal—the two countries that accrued the largest inflows of treasure in the early modern period—did not become the first capitalist economies; instead, they experienced long periods of economic stagnation following their imperial windfalls.

By contrast, England, which had relatively limited imperial exploits in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, is the site where historians can most clearly locate a transition to capitalist social relations in the sense Marx analyzed—that is, a transformation of agricultural class structures and labor relations that pushed peasants into market dependence and competitive production.

On the other hand, Chibber insists that explanations centered on plunder and colonial riches are incoherent within a Marxian framework. The reason is straightforward: having piles of money or gold on hand does not cause capitalist social relations to emerge. What is distinctive about capitalism—what makes capitalism capitalism—is how money or other assets are used, namely, as capital: as money thrown into a market as investment to generate more money.

As Marx and later historians have emphasized, markets already existed in feudal Europe, but they were not the central engines of economic activity, and their logics did not dominate the social order. In the Middle Ages, the lower classes tended to produce for subsistence, while lords lived off rents. When lords could not live off rents, they tended to live off spoils of (intra-European) plunder. In these societies, exchange occurred; markets existed; but the overall reproduction of the social order—the driving logic of economic activity—was not market-mediated. This is why feudalism was not capitalism.

Capitalism emerges not when riches become abundant but when money is used in a capitalist fashion, that is, as productive investment.

From a Marxian perspective, capitalism emerges not when riches become abundant but when money is used in a capitalist fashion, that is, as productive investment. When this occurs, market relations proliferate, a shift in class structures gains ground and ties producers to markets and profit-driven production; production becomes commodity production. It is only when peasants lose independent access to land and are compelled into competitive market relations that wage labor is generalized and capitalism proper emerges.

This process began in England in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, prior to England’s emergence as an imperial hegemon; and it did not take hold in Spain and Portugal until long after their imperial hegemony had been eclipsed. Thus, Chibber concludes, capitalism did not require New World colonialism to get off the ground. If anything, New World colonial exploits retarded capitalist development in Southwestern Europe.

Logics of consolidation

Now, I’m not at all well-positioned to evaluate these arguments. I’m not an historian of capitalism. But a few thoughts on how Chibber’s arguments look when refracted through Baker’s book may still be worth considering.

First, the question Chibber poses—whether colonial plunder was necessary to capitalism’s European genesis—can be separated from a different, and in some ways orthogonal question about what kinds of coercive social relations capitalism has required in order to reproduce itself across space and time, and what kinds of counterrevolutionary innovations have been generated when those relations are contested. This is the question Baker is after. I also take it to be the question many contemporary theorists of “primitive accumulation” are after. And even if we grant Chibber’s origin-story, it’s not clear what’s wrong with this question or the way these folks respond to it.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume Chibber is right and capitalist social relations first emerged in England for reasons that cannot be explained by inflows of plundered bullion from the New World. It would hardly follow that colonialism and slavery were contingent supplements to an already self-sustaining system. Whatever explains its genesis at the threshold of modernity, few historians would deny that capitalism’s consolidation as a global economic force in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was fueled by the plantations of the American South.

Baker suggests that attending to the incessant insurgency waged against antebellum US slavery “makes legible the unfinished, contingent, and fragile character of racial capitalism, which its ideologies disavow.” That is, the entangled histories of resistance and counter-mobilization expose capitalism as an “always embattled and uncertain project.” At the same time, his account of “white counterrevolution” keeps in view the logics of consolidation that allow embattled structures of domination to retrench and reproduce themselves: in short, to become hegemonic. From this perspective, if the enclosures of feudal England made capitalism possible in the fifteenth century, it seems likely that a key condition of capitalism’s consolidation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was the relative success of the “white counterrevolution” Baker tracks and theorizes.

“Primitive accumulation” may be less a discrete prehistory than a repertoire of strategies that can be redeployed whenever the “mute compulsion” of the market falters or proves insufficient.

Put differently, Baker’s intervention shifts attention away from the question of origins and toward the recurring issue of capitalism’s plasticity and ongoing reproduction. The dialectic he reconstructs—insurrection from below producing recomposition and realignments above—helps illuminate why “primitive accumulation” may be less fruitfully understood as a discrete prehistory than as a repertoire of strategies that can be redeployed whenever the “mute compulsion” of the market falters or proves insufficient. That is also why Fabbri’s category of preventive counterrevolution feels so relevant here: it names the political logic by which the ruling classes respond not only to actual revolutionary rupture, but to the prospect of it, using coercion to foreclose alternative futures before they can coalesce.

Whatever one thinks about the causal story of capitalism’s emergence, Baker’s book presses a different claim that is hard to shake: that the history of emancipation cannot be told apart from the history of counterrevolutionary consolidation—and that the coercive “exceptions” of capitalist rule have a tendency, in moments of crisis, to become its governing norm.

Thanks for this post. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the overlapping historical streams that fed the roots of contemporary capitalism is vital to the success of activists and groups engaged in the continuing project of dismantling the current iteration and supplanting it with a more just, durable, and sustainable system.

are these posts (or the material in them) all incoporated into the class you're teaching this winter?